Do we Need Real World Data or Should We Just Stick with RCTs?

Real World Data: Do we Really Need It?

I’m a big fan of evidence. And I’m a bigger fan of really good evidence compared to mediocre evidence. I occasionally find myself sometimes unable to sleep when I to see a well-designed randomized controlled trial that answers key questions in the world of hair loss. On the contrary, I find myself extremely nauseated and sometimes unable to eat or function when I come across a poorly designed study that generates false conclusions. (I have seen two in the last two weeks).

Today I’d like to highlight why we need a variety of study types in the hair research world … and not just the much loved randomized controlled trials.

We often give randomized controlled trials a big thumbs up when it comes to the types of trials we need to generate good evidence. In fact, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are commonly viewed as the best research method to make a meaningful change in how things are done in medicine.

Today, I’d like to discuss briefly why I feel we need both RCTs and “Real World” Studies in Hair Loss. The two types of studies are really quite complementary.

What are RCTs and What are Real World Studies?

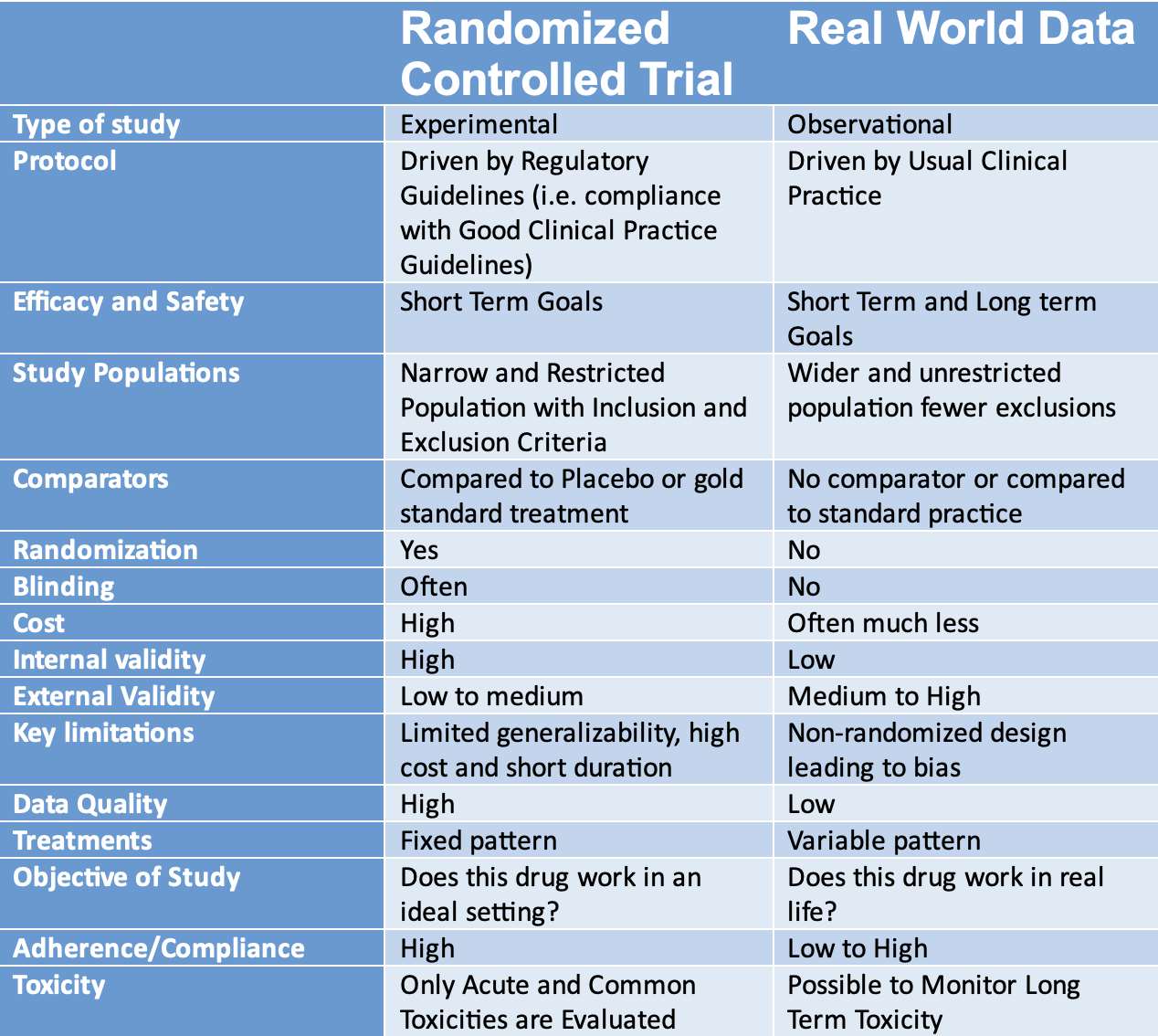

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) are prospective studies that measure the effectiveness of a specific intervention or treatment. It is a study design that randomly assigns participants into an experimental group or a control group.

On the other hands, real world data (RWD) is defined by the FDA as the type of data that is collected from routine patient care including data from charts, electronic health records, medical claims data, data from product or disease registries, and other sources.

Let’s take a look at some of the benefits and concerns about RCT’s and RWD

The Benefits of RCTs

RCT are generally viewed as being the best method to try to determine “cause and effect” relationships. They provide the most reliable evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention.

We can all agree that RCTs are widely viewed as being the “gold standard” by which the efficacy of a drug is evaluated. You are probably well aware that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires RCTs for most drugs to be approved.

In fact, the AMA Manual of Style (an important “go to” guide author researchers in medicine) notes that randomized clinical trials (RCTs) “generally yield the strongest inferences about the effects of medical treatments.” The AMA Manual of Style instructs that “randomized trials may use terms such as effect and causal relationship.” This differs from observational type studies where the AMA Manual of Style states clearly that observational studies “cannot lead to causal inferences” thus “should be described in terms of association or correlation and should avoid cause-and effect wording.”

RCT’s are great because they minimize the chances of allocation bias and confounding. It is the best type of study to reduce bias and control for confounding. It is the only design to account for unknown variables.

What are the problems with RCT?

Despite their many benefits, there are downsides to RCTs.

RCTs are highly controlled. They are standardized and highly monitored. They include only specific patient populations and exclude others. So that means the results may not be completely generalizable to other groups. They offer proof of efficacy only under very controlled conditions. It is possible that results might not reflect the effects of the treatment in real world settings or in other groups of individuals who were not enrolled in the trial.

RCTs are also very costly!!!!!! RCTs have study coordinators and study nurses. They are carefully controlled at each step. Costs rise quickly.

RCTs generally only evaluate short-term outcomes. So - they are not studies that provide long term side effect data! If you want to know if a drug increases the risk of cancer over the long run or heart disease or Parkinson’s … you’ll probably not be getting that from a typical short term RCT. There is probably never going to be randomized double blind placebo controlled hair study that is going to show you that use of a hair loss drug comes with the bad side effects of increasing cancer. RCTs are just not long enough in duration.

RCTs often use study endpoints that are going to be best to prove a drug helps. If a study can show that an endpoint occurs more commonly or less commonly with use of a drug compared to placebo or another comparator, well you have success! Success often means that regulatory approval is to be that much more likely.

RCTs have their own bias. Trials can have many types of bias including allocation bias, performance bias, assessment bias, attrition bias.

Now that said, mandatory trial registration nowadays and more stringent reporting guidelines and journal requirements seem to be improving the applicability of RCTs in recent years. Nevertheless, relatively high probabilities of bias remain, particularly in journals with lower impact factors.

Not Everyone Is Quite So Infatuated with RCTs.

Before, we talk about real world data, let’s just focus on the potential problems with RCTs in the world. First, let me say that probably the most important thing one can do when evaluating the published medical literature is to approach it with a slight degree of skepticism. If you lived your entire life like you need to function as an evaluator of the medical literature, it would not be much fun. In life, one really needs to be accepting and open and trust people for the goodness they bring to the world. In medical science however, it’s not quite like that. One needs to be critical and skeptical, and validate things from various angles.

In 2018, Krauss shared a view that all randomized controlled trials have bias. I tell my own trainees that it’s worth a read as they develop for themselves their own sense of how to approach the medical literature.

Krauss reviewed 10 of the most cited RCTs in the world. Most of these have influenced public policy. Krauss concluded that these 10 world-leading RCTs produce biased results by illustrating that participants’ background traits (that affect outcomes) are often poorly distributed between trial groups, that the trials often neglect alternative factors contributing to their main reported outcome and, among many other issues, that the trials are often only partially blinded or unblinded. All in all, Krauss’s main point is that researchers and policymakers need to become better aware of the broader set of assumptions, biases and limitations in trials.

Some RCTs are A bit Flawed, Some are Seriously Flawed and Some are Fake

There are some pretty nice RCTs out there in the world of the medical literature. However, one thing they don’t teach you in medical school is that some are not so good. It is now thought by some that one of every 4 RCTs contain so many problems that their findings should be ignored. Some are felt to be fake. These find their way into systematic reviews and changes practice!!! Some of the world’s leaders in clinical trials have even estimated that up to 40 % of RCTs are untrustworthy. These are touchy subjects. To listen to a very informative podcast, click on the link below.

Meet Dr John Carlisle: Anesthesiologist and Data Detective

If you don’t know about John Carlisle, it’s probably time that you do. Dr Carlisle is a UK anesthesiologist (anaesthetist) who took on a course in his professional life to better understand how many studies are false and how one might spot them. You can read an interesting review of John here:

John Carlisle works as an anesthesiologist and also as editor of the journal Anaesthesia. In 2017, he decided to take a closer look all the manuscripts he handled that reported a randomized controlled trial (RCT) . Over three years, he reviewed over 500 studies. For most of the trials, he could not get access to the individual patient data (IPD) from the trial.

However, for more than 150 trials, Carlisle was able to get access to anonymized individual participant data (IPD). By studying the IPD data in detail, Dr Carlisle felt that 44% of these trials contained at least some flawed data: impossible statistics, incorrect calculations or duplicated numbers or figures. He concluded that 26% of the papers had problems that were so widespread that the trial was impossible to trust. He said that this possibly came about either because the authors were incompetent, or because the authors had faked the data.

Carlisle went on to call these trials ‘zombie’ trials. Zombie trials look sort of like real research trials, but when you look closer they are not. They are hollow shells, masquerading as reliable information. Dr Carlisle estimated that 1 in 10 trials could be zombie trials.

Dr Carlisle proposes that seeing the independent patient data is really important to spot something is not right. For example, when Carlisle did not have the permission to access a trial’s raw data and could study only the aggregated information in the summary tables it seemed that only about 1% of these cases were zombies, and 2% had flawed data. when all data is put out on the table, Carlisle found the number went way up.

In the 2021 paper published in Anaesthesia, Carlisle write in the conclusion of his abstract “I think journals should assume that all submitted papers are potentially flawed and editors should review individual patient data before publishing randomised controlled trials.”

Other specialists have shared their own views. One author, Ben Mol, who specializes in obstetrics and gynaecology in Australia, argues that as many as 20–30% of the RCTs included in systematic reviews in women’s health are suspect. Another researcher, Ian Roberts, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine states that “if you search for all randomized trials on a topic, about a third of the trials will be fabricated”

So clearly we have a high proportion of randomized controlled trials and an unfortunate number of randomized confabulated trials.

What are the benefits of Real World Studies?

Real world studies are the studies that come from the clinical setting. RWD is that data that comes from opening up patient charts and figuring out how patients were treated and what outcomes they had. Real-world observational data can often provide additional very welcomed complementary data to RCTs. They provide us with important evidence by answering important questions on a number of treatment effects in real clinical practice that don’t get answered by RCTs.

These types of RWD studies provide realistic adherence data. That’s because there are no clinical trial coordinators and study nurses paid to oversee things in the real world. Patients in the real world forget their pills, patients don’t take things regularly. Patients often skip treatments.

Real world studies allow long term monitoring and can therefore detect rare side effects.

They are less expensive. They can be used to determine risk factors and prognostic factors. They can identify secular trends. They can be used to study rare exposures and rare occurrences. They can be used to generate risk models.

What are the Problems or Disadvantages with Real World Studies?

Real world studies have their limitations and problems. As the name suggests, they are not randomized. The lack of patient selection can lead to confounding factors. Real world studies are not subject to trial registration. They are more likely to be subjected to p hacking or p fishing, subjective analyses and publication bias.

Do we Need Real World Data or Should We Just Stick with RCTs?

In summary, we need both RCT data and real world data. Both are complementary! Both have their limitations and concerns and it is up to researchers, journals, and ethics boards, and trial registration committees and all of us to help understand the limitations.

Summary Table: RCT vs RWD

REFERENCE

Krauss A. Why all randomised controlled trials produce biased results. Ann Med. 2018 Jun;50(4):312-322.

Van Noorden R. Medicine is plagued by untrustworthy clinical trials. How many studies are faked or flawed? Nature. 2023 Jul;619(7970):454-458.

Carlisle JB. False individual patient data and zombie randomised controlled trials submitted to Anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2021 Apr;76(4):472-479.

This article was written by Dr. Jeff Donovan, a Canadian and US board certified dermatologist specializing exclusively in hair loss.