Treatment of Scarring Alopecia in Pregnancy

Treating Scarring Alopecia During Pregnancy: What options are available?

The are about 10 different scarring alopecias that are typically seen in a busy hair clinic. Theses include lichen planopialaris, frontal fibrosing alopecia, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, discoid lupus, folliculitis decalvans, dissecting cellulitis and pseudopelade. The various types of scarring alopecias are treated slightly differently which makes it important to first and foremost get an accurate diagnosis. For example, frontal fibrossing alopecia is treated differently from folliculitis decalvans and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is treated different from discoid lupus. In total, there area about 25 treatments available for the various forms of scarring alopecia. Some treatments work better than others.

When it comes to treating scarring alopecia during pregnancy, the question changes from what works best to what works best and is still safe for the pregnant mother to be.

Data collected from the general population have shown that many women do use certain medications during pregnancy. While data specifically from patients with scarring alopecia is not know if it likely similar in trend. For example, a study by Mitchell et al in 2011 showed that 50 % of pregnant women report taking at least one medication during pregnancy, with the average being 2.6 prescriptions at any time during pregnancy.

What treatments are NOT permitted in pregnancy?

Many treatments are not permitted in pregnancy due to the potential harm it can bring a developing baby. In general, no patient with scarring alopecia should be using any medication for their hair loss without first consulting with her physician or care providers. This basic principle can’t be overstated.

The treatments that are NOT permitted during pregnancy are many and include treatments such as doxycycline, tetracycline, minocycline, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept, Myfortic), topical finasteride, oral finasteride, dutasteride, apremilast (Otezla), spironolactone, bicalutamide, flutamide, isotretinoin, topical minoxidil (Rogaine) and oral minoxidil. At present, there is not enough evidence to support the use of JAK inhibitors for treating scarring alopecia during pregnancy although this continues to be studied. I recommend stopping 10-12 weeks before any pregnancy. Furthermore, I do not use PRP in pregnancy. I don’t recommend use of azathioprine in my own patient during pregnancy although emerging data suggest it may be much safer than once understood. Indeed, both the British Society of Rheumatology and the EULAR recently concluded that AZA is compatible with pregnancy (see Götestam Skorpen C et al., 2016).

I do not recommend use of TNF inhibitors in pregnancy as some studies have suggested an increased risk of congenital malformations and preterm birth. There are no studies of TNF inhibitors use in pregnant women with hair loss disorders.

This list of contraindicated medications that I have listed above is by no means exhaustive. Every patient with scarring alopecia should carefully review with their physicians the safety of any medication they plan to use while pregnant.

What treatments are sometimes permitted?

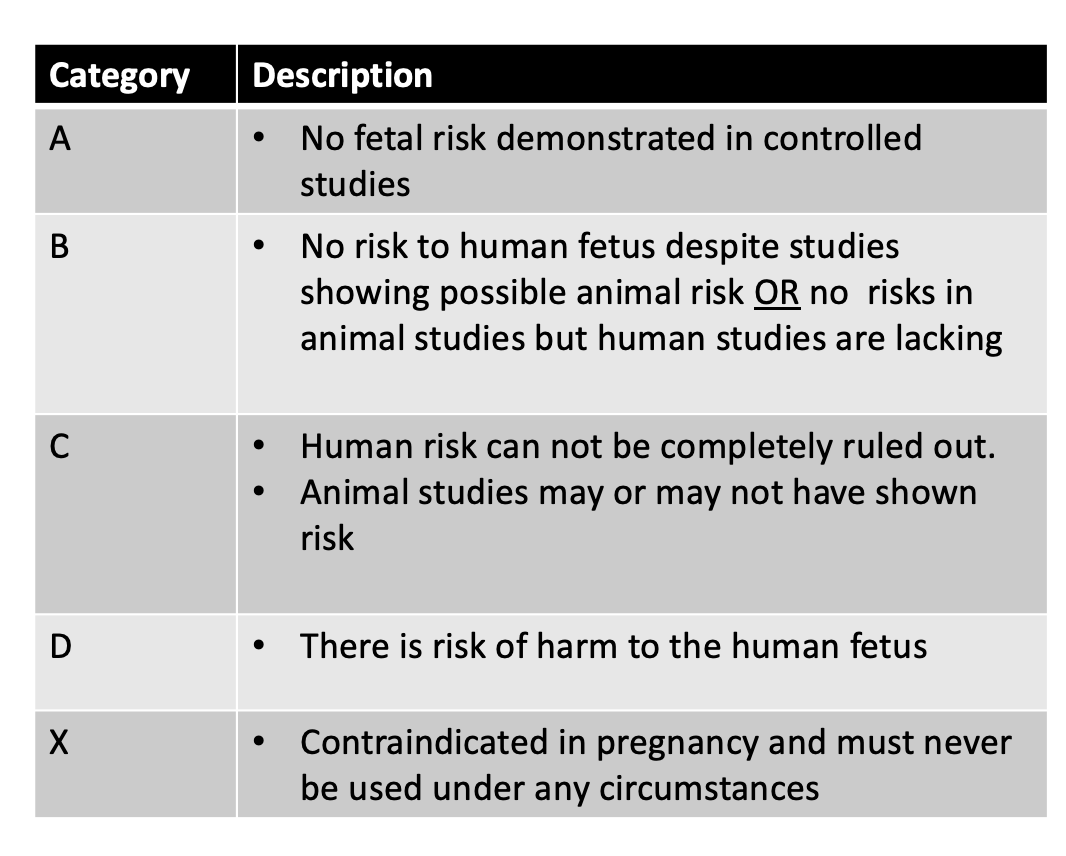

Some treatments may be possible in pregnancy if the physician together with the patient come to feel that the benefits of treatment outweigh any known risks. Many patients want simple straight forward answers - unfortunately those don’t always exist given that large studies in pregnancy have not typically been conducted. What we do know is that a certain medications seem fairly safe based on all the evidence that has been collected to date. Medications are often given safety ratings (A, B, C, D, X) although this system of classifying drugs is becoming less commonly used.

Every single pregnant woman is strongly advised to review the safety of potential hair loss medications on a case by case basis with her doctor before using. There is no template and no blanket statements that applies to all patients as far as which treatments can be used. However, a few points are helpful:

1) Topical betamethasone valerate 0.1 % lotion (Former FDA Pregnancy Category C)

There is no evidence that occasional use of very small amounts of betamethasone valerate 0.1 % lotion brings harm to a fetus. Prolonged uses of potent steroids, however, may lead to some absorption and so such use is discouraged. Any pregnant individual considering using topical betamethasone valerate lotion for treatment of their scarring alopecia needs to review the situation with their own doctor. In my practice, low doses such as 1 mL once to twice weekly of topical betamethasone valerate 0.1 % lotion is permitted with no more than 5 applications monthly without frequent review. Patients with diabetes or gestational diabetes will need closer monitoring. More frequent use of betamethasone valerate 0.1 % lotion can sometimes permitted. Rarely, will I recommend use of stronger topical steroid such as clobetasol. Betamethasone valerate 0.1 % lotion is given pregnancy category C.

I don’t generally perform steroid injections with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) during pregnancy.

2) Topical clindamycin 2% (Former FDA Pregnancy Category B)

The additional of additives such as 2% clindamycin powder to the betametasone valerate 0.1 % scalp lotion can be helpful for some pregnant women with bacterial related scarring alpacas such as folliculitis decalvans. Topical clindamcyin has been categorized as pregnancy category B by the FDA in their older classification system.

3) Oral cephalexin (Former FDA Pregnancy Category B)

Many topical and oral antibiotics are not permitted in pregnancy. Oral cephalexin is an antibiotic and is occasionally used to treat flares of folliculitis decalvans during pregnancy that can not be controlled with use of topical clindamycin and/or betamethasone. All antibiotics require discussion of the risk and benefits with the treating physician. Oral cephalexin is given pregnancy category B. When its use is felt to provide greater potential benefits than any of the known risks, it is typically given for a period of 2 weeks. Longer courses of oral cephalexin are not typically recommended.

4) Topical tarcroliumus ointment (Former FDA Pregnancy Category C)

Topical tacrolimus is not typically used in pregnancy for patients with scarring alopecia. However, in cases of scarring alopecia that are not settling in pregnancy, this medication could be one for a patient to discuss. Topical tacrolimus is given pregnancy category C

We have learned most of what we know about topical tacrolimus safety in pregnancy from studies pertaining to the use of oral tacrolimus pills in pregnancy. Most of these studies comes from organ transplant patients who continue to use tacrolimus pills all the way through their pregnancy. Of the 200 or so pregant patients who have used oral tacrolimus, Dr Nevers and colleagues report that most women had good pregnancy outcomes, with no evidence of increased risk of congenital malformations. However, pregnant women using tacrolimus pills report higher rates of preterm delivery and low birth weight. There are also several reports of transient neonatal hyperkalemia (high potassium levels in the blood) and kidney problems. Such kidney problems fortunately resolved in infancy without further adverse effects.

As Dr Nevers and colleagues report, “the current available information does not suggest that tacrolimus increases the risk of major congenital malformations above the baseline risk in the general population.” When one considers that very little tacrolimus gets absorbed into the blood stream when applied topically to the scalp, the safety margin becomes even greater for those using topical tacrolimus (Protopic).

In my practice, some patients will use pea sized amount of tacrolimus to control refractory scarring alopecias during pregnancy. Use should be limited to a few times per month.

5) Low level laser therapy with 655 nm red light (not formally assigned)

At present, we have no evidence that use of red light laser helmets, or caps or brushes on the scalp in the manner outlined by the manufacturer brings harm to pregnancy.

6) Oral antihistamines

Oral antihistamines can be helpful in managing some aspects of scarring alopecia. For many, the use of antihistamines helps reduce itching. For some scarring alopecias (such as lichen planopilaris), use of antihistamines, such as cetirizine may actually reduce scarring alopecia disease activity. (See Cetirizine in Lichen Planopilaris).

Any pregnant women with scarring alopecia should carefully review the use of antihistamines with her physician before starting. Many of the first- and second-generation antihistamines do not appear to increase fetal risk in any trimester. My preferred antihistamines are diphenhydramine (Benadryl), cetirizine, (Zyrtec and Reactine) and loratadine (Claritin) give that these are all classed as former pregnancy category B.

7) Anti-dandruff shampoos

Seborrheic dermatitis is common in the setting of scarring alopecia and this frequently requires use of an antidandruff shampoo. We don't have much information on the safety of anti-dandruff shampoos in pregnancy. The data would suggest that periodic use of zinc pyrithione shampoos and ciclopirox olamine shampoos have reasonably good safety and these are frequently my top choices for many of my own patients. If dandruff (or seborrheic dermatitis) is troublesome, I generally advise use once every 2 weeks and to be left on the scalp for 60 seconds before rinsing off. Small amounts of betamethasone valerate scalp lotion can be used once weekly if itching persists.

What I usually don't recommend to my patients. Ketoconazole shampoos don't have much in the way of data. Patients interested in using should check with their OB or the physician caring for the pregnancy. There is no good data to really suggest a problem with periodic use of topical shampoos containing ketoconazole. It’s classified as former class C. However, it's not the top choice for my practice as they have the potential to affect testosterone synthesis. Oral ketoconaole is certainly not advised in pregnancy. Oral ketoconanzole increases the risk of cardiovascular, skeletal, craniofacial and neurological problems in many studies. I don't recommend coal tar shampoos during pregnancy either. Animal studies show that high doses are associated with perinatal mortality, cleft palate, small lungs and other developmental issues. I avoid them in my practice.

8) Oral Immunosuppressive or Imunnomodulatory Medications

The use of certain oral immunonsuppressive medications may be possible in pregnancy but this should always be handled on a case by case basis and always in conjunction with the advice of the obsterician/gynaecologist, family physician and other treating physicians (rheumatologist, etc). Most oral immunosuppressants are not completely “risk free” and the known risks must be balance against the benefits that may come from the use of such treatments.

a) Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil). The use of hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) may be permitted in some cases in pregnant patients who are not able to obtain control of their scarring alopecia with use of topical steroids and topical tacrolimus. However, the use of hydroxychhloroquine in pregnancy may not be completely risk free. An extremely important study to know about is the 2003 study by Costedoat-Chalumeau and colleagues in which the outcomes of 133 pregnancies using hydroxychlorquine were compared to 70 pregnancies in women who did not use hydroxychlroquine. There was no difference in pregnancy outcomes between the two groups. However, a recent study which compared 2045 hydroxychloroquine-exposed pregnancies and 3,198,589 pregnancies in patients who did not use hydroxychloroquine suggested a slight increased risk of malformations in hydroxychloroquine users. Concerns exist over possibility anomalies of the fetus eyes and ears in pregnant women using hydroxychloroquine.

The FDA did not ever assign a pregnancy class to hydroxychoroquine

b) Cyclosporine (Former FDA pregnancy Catgeory C). Cyclosporine use among pregnant patients with scarring alopecia is not common. Similar to other oral medications, the use of cyclosporine must be on a case by case basis and only in conjunction with thorough discussion with the patient and her specialists. Cyclosporine too is not completely risk free and may be associated with premature delivery and low birthweight infants. Comorbidities such as hypertension, pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus are also reported at higher incidences than the general population.

c) Corticosteroids. I rarely if ever will prescribe prednisone in pregnancy. If my patient is started on prednisone it is usually after a long discussion with the patient and her rheumatologist, dermatologist or other specialist. Oral prednisone is classed as pregnanc y class C and are know to give an increased risk of birth defects in both human and animal studies. Cleft palate is one such well studied issue. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, use of steroids in pregnancy can increase the risk of premature delivery. Most specialists will prescribe in pregnancy if absolutely needed but usually only in the second and third trimesters. Prednisone is best avoided in the first trimester when the risk of birth defects (cleft palate especially) is the highest.

REFERENCES

Christopher V et al. Pregnancy outcome after liver transplantation: a single-center experience of 71 pregnancies in 45 recipients. Liver Transpl 2006;12(7):1138-43.

Clowse M et al. Pregnancy Outcomes in the Tofacitinib Safety Databases for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Psoriasis Drug Saf. 2016; 39: 755–762.

Costedoat-Chalumeau et al. Safety of hydroxychloroquine in pregnant patients with connective tissue diseases: a study of one hundred thirty-three cases compared with a control group. Arthritis Rheum 2003 Nov;48(11):3207-11.

Curtin SC, et al. Pregnancy rates for U.S. women continue to drop. NCHS data brief, no 136. National Center for Health Statistics. 2013.

Götestam Skorpen C et al. The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:795–810.

Huybrechts KF et al. Hydroxychloroquine early in pregnancy and risk of birth defects. Am J Ob Gynecol. 2020 Sep 19;S0002-9378(20)31064-4.

Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z et al. Outcome of four high-risk pregnancies in female liver transplant recipients on tacrolimus immunosuppression. Transplant Proc 2006;38(1):255-7.

Jain A et al. Pregnancy after liver transplantation under tacrolimus. Transplantation 1997;64(4):559-65.

Kainz A et al. Review of the course and outcome of 100 pregnancies in 84 women treated with tacrolimus. Transplantation2000;70(12):1718-21.

Jain AB et al. Pregnancy after liver transplantation with tacrolimus immunosuppression: a single center’s experience update at 13 years. Transplantation 2003;76(5):827-32.

Jain AB et al. Pregnancy after kidney and kidney-pancreas transplantation under tacrolimus: a single center’s experience. Transplantation 2004;77(6):897-902.

Johansen CB et al. The Use and Safety of TNF Inhibitors during Pregnancy in Women with Psoriasis: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 May; 19(5): 1349.

Mitchell AA et al.; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol2011;205:51.e1–8.

Nevers W et al. Safety of tacrolimus in pregnancy. Canadian Family Physician October 2014, 60 (10) 905-906;

Vellanki K et al. Pregnancy in chronic kidney disease Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013 May;20(3):223-8.

This article was written by Dr. Jeff Donovan, a Canadian and US board certified dermatologist specializing exclusively in hair loss.